Building Resilience and Adapting to Climate Change: Synthesis of the 2021 BRACC Evaluation

In 2021, after just over 2.5 years of implementation, an evaluation was conducted on Building Resilience and Adapting to Climate Change (BRACC) programme.

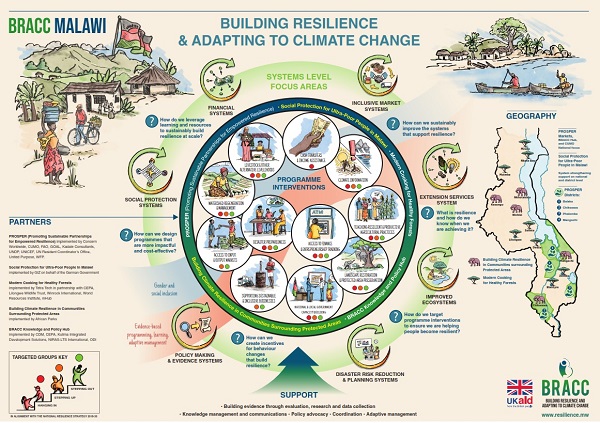

BRACC is a five-year, £90.6 million programme funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) that provides targeted support in the most vulnerable districts, communities and high priority catchments in Malawi, to strengthen the resilience of poor and vulnerable households to shocks and reduce their annual dependence on humanitarian aid. The programme comprises five components each implemented by different organisations/consortia:

- Component 1: Climate-resilient livelihoods (PROSPER)

- Component 2: Provision of a scalable safety net or ‘crisis modifier’ (PROSPER)

- Component 3: Strengthening social protection systems (GIZ)

- Component 4: Natural resource management (AP and MCHF)

- Component 5: Evidence, knowledge and policy influence (BRACC Hub).

Recent ODA cuts have led to several parts of the BRACC programme being closed early in 2021. The UN-led activities under PROSPER, targeting the most vulnerable families, will be continued in Balaka and Phalombe until 2023. This will cover climate services, disaster risk reduction, market support, access to finance, watershed management and agricultural training – but without accompanying cash transfers. The 2021 evaluation, initially intended as a mid-line, thus serves as a de facto endline for several of the components.

The evaluation shows that there is stronger evidence for household-level resilience outcomes (such as intensified and diversified agricultural production and improved nutrition) - as would be expected at this stage in the programme; and weaker evidence for system-wide changes (such as inclusive access to markets, reduced exposure to drought and floods, and strengthened governance capacity to prepare for, plan, monitor and respond to shocks, and develop a more shock-sensitive social protection system) that are expected to take longer to develop.

A number of factors contributed to the successes and achievements: these include layering interventions, working with local leaders, ownership by participants and the wealth-category targeting approach (aligned with the National Resilience Strategy). Lack of resources to participate was a major barrier – particularly for the ‘hanging in’ (poorest) wealth category, and ongoing environmental and climate shocks and stresses have the potential to undermine gains.

In terms of programme design, training and knowledge-based approaches (as opposed to asset transfer) increase the likelihood of sustainability – but the short duration to date impedes behaviour change becoming embedded. Targeting different wealth categories allows tailoring of support to meet needs. However, with consumption support only given to the ‘hanging in’ (poorest) wealth category, marginalised groups (including female-headed households) were under-targeted, especially considering that they often had the strongest impact on agricultural and nutrition outputs.

In terms of overall findings regarding attainment of resilience, the evaluation finds that resilience is context-specific and needs to be adaptive in the context of changing climate conditions. Resilience measurement also needs to take this context into account. Reducing poverty or building wealth alone do not necessarily increase resilience to climate stresses, so integrated approaches are crucial.